As the spring season continues, May could prove to be of great interest for stargazers and space enthusiasts – with a pair of potentially active meteor showers opening and closing the month.

“Meteors aren’t uncommon,” Bill Cooke said, who leads NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. “Earth is bombarded every day by millions of bits of interplanetary detritus speeding through our solar system.”

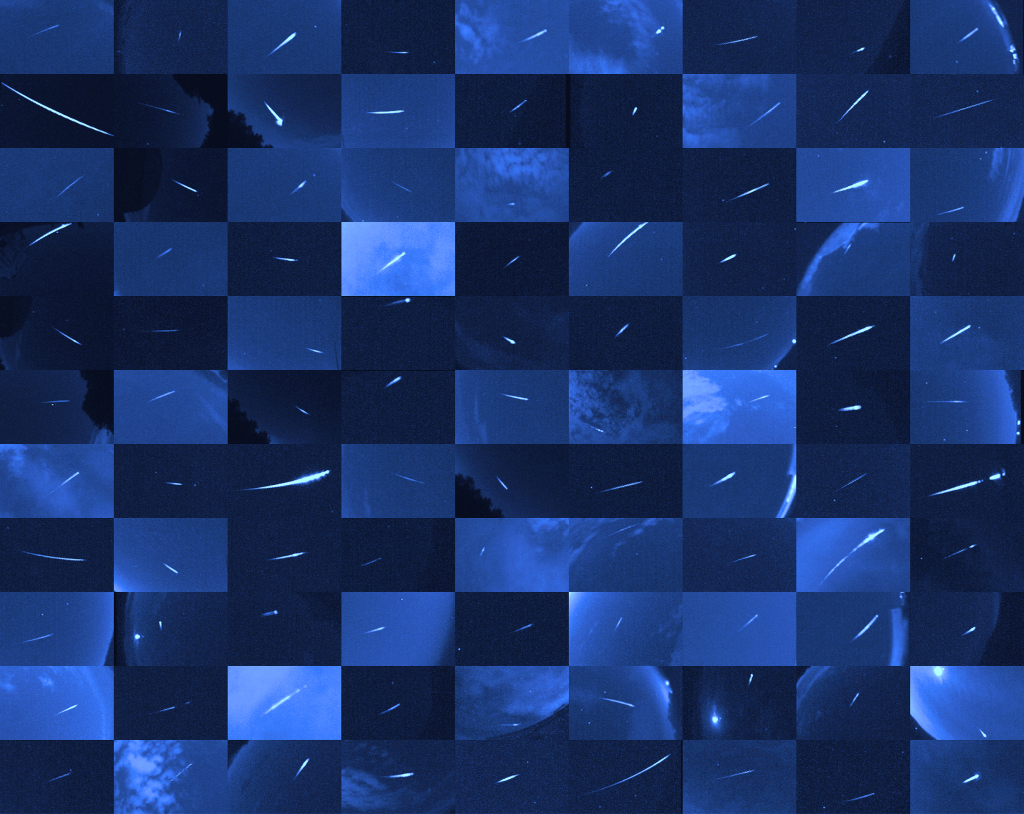

Credits: NASA All Sky Fireball Network

Most particles are no bigger than dust and sand. Hitting the upper atmosphere at speeds up to 45 miles per second, they flare and burn up. On any given night, the average person can see from 4 to 8 meteors per hour. Meteor showers, however, are caused by streams of comet and asteroid debris, which create many more flashes and streaks of light as Earth passes through the debris field.

“It’s a perfect opportunity for space enthusiasts to get out and experience one of nature’s most vivid light shows,” Cooke said.

Eta Aquariids (May 5-6)

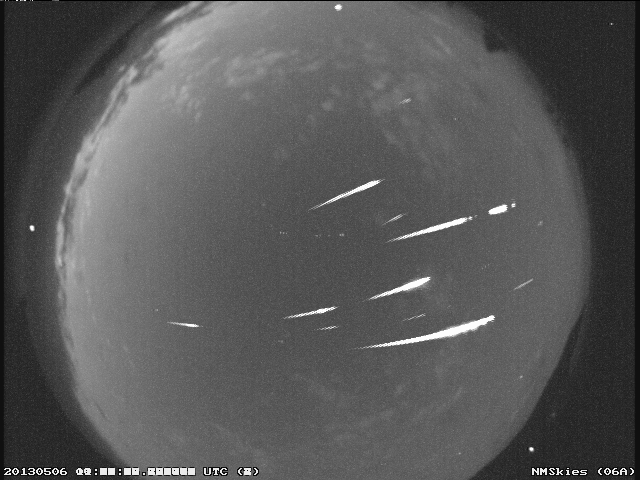

First up, on the night of May 5 and early hours of May 6, around 3:00 am CDT, is the eta Aquariid shower, caused by the annual encounter with debris from Halley’s comet – remnants of the comet’s tour through the solar system once every 75 or 76 years. Its radiant – or the point in the night sky from which the meteor shower appears to originate – is the constellation Aquarius. The shower is named for the brightest star in that constellation, eta Aquarii.

Credits: NASA Meteoroid Environment Office

Until Halley’s comet is next visible from Earth in 2061, only the eta Aquariids – and their fall counterpart, the Orionid meteor shower, which is visible each October – mark the passage of this solar system visitor.

“It will be interesting to see if the rates are low this year, or if we will get a spike in numbers before next year’s forecast outburst,” Cooke said.

The annual meteor shower has the best rates for those in the Southern Hemisphere, but even in the Northern Hemisphere, if weather conditions are right, there is a possibility of seeing up to 30 meteors per hour. The waxing crescent Moon will set before the eta Aquariid radiant gets high in the sky, leaving dark skies for what should be an excellent show. Best viewing happens after 3 AM local time, so get up early.

Tau Herculids (May 30-31)

A possible newcomer this year is the tau Herculid shower, forecast to peak on the night of May 30 and early morning of May 31.

Back in 1930, German observers Arnold Schwassmann and Arno Arthur Wachmann discovered a comet known as 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann, or “SW3, which orbited the Sun every 5.4 years. Being so faint, SW3 wasn’t seen again until the late 1970s, seeming pretty normal until 1995, when astronomers realized the comet had become about 600 times brighter and went from a faint smudge to being visible with the naked eye during its passage. Upon further investigation, astronomers realized SW3 had shattered into several pieces, littering its own orbital trail with debris. By the time it passed our way again in 2006, it was in nearly 70 pieces, and has continued to fragment further since then.

If it makes it to us this year, the debris from SW3 will strike Earth’s atmosphere very slowly, traveling at just 10 miles per second – which means much fainter meteors than those belonging to the eta Aquariids. But North American stargazers are taking particular note this year because the tau Herculid radiant will be high in the night sky at the forecast peak time. Even better, the Moon is new, so there will be no moonlight to wash out the faint meteors.

“This is going to be an all or nothing event. If the debris from SW3 was traveling more than 220 miles per hour when it separated from the comet, we might see a nice meteor shower. If the debris had slower ejection speeds, then nothing will make it to Earth and there will be no meteors from this comet,” Cooke said.

Learn more about meteors and meteorites. Also, if you want to know what else is in the sky for May, check out the latest “What’s Up” video from Jet Propulsion Laboratory:

Enjoy all this month has to offer as you watch the skies!

by Rick Smith

source: blogs.nasa.gov